My First Death Cafe

A write up of Death Cafe in Fairfax, California

Saturday, I talked with a group of strangers about death — it was the most intimate and meaningful conversation of my week.

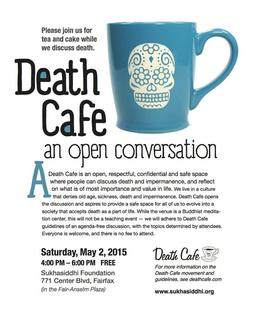

This was my first Death Cafe, and the first one for most of the 50 to 60 people gathered at the Sukhasiddhi Foundation, a Buddhist meditation center in Fairfax, California.

In small groups, mostly four people sitting around café tables with coffee and pastries, we discussed hypothetical questions —

- If you knew you had twelve months to live, what would you do?

- If someone you were close to died and you could somehow speak to on from the other side, what would you ask them?

- How would you like to die and why?

There were twelve tables around the room, plus a group sitting on pillows in the middle. Each person got three minutes to answer the question, then there was a gong, and it was on to the next person. After the small group discussions, the facilitator opened it up to the larger group and moved around the room with a microphone.

Most participants were middle-aged, middle-class, and white. A few were under fifty. More than a few appeared to be over seventy.

Since launching in London in 2011, there have been more than 1,863 Death Cafes. As of this past Saturday. In the several days since, there have been at least a dozen more — in Zurich, Seattle, St. Louis, Toronto, and Auckland, to name a few locations. Most are small gatherings, according to our facilitator in Fairfax. For our gathering, they had to find additional chairs and pillows to accommodate the crowd.

The concept is simple. People gather to talk about death, with the aim of “increasing the awareness of death to help people make the most of their (finite) lives.”

Death Cafe is a “social franchise” — that is, anyone who signs up to use the guide and principles can use the name “Death Cafe.” There’s no staff and no profit.

In our group, there seemed to be broad range of perspectives on death and what comes after. One person, for example, said that the second question implies there is another side after death and she doesn’t believe there is. What everyone seemed to agree on, however, was that it would be a good thing if we were more comfortable as individuals, families, and societies discussing death.

That’s why I attended. Last summer, my mother, who will be 92 at the end of this month, was coughing up blood and ended up in a Chicago hospital for two weeks. All five of her children, as well as most of her grandchildren, convened from California, New Mexico, Michigan, Illinois, and New York. We thought she might die. So did the doctors. Because she had a DNR (do not resuscitate) on file, we had to discuss almost every procedure. How much intervention? Did we want a breathing tube down her throat if it was necessary? No. What about antibiotics? Yes.

I also went because I am in the early stages of writing a novel about a man whose father, suffering from cancer and dementia, asks his son to help him end his life. (Here’s a draft of Quality of Life, Chapter 1: The Weight of a Nitrogen Tank.)

Several people shared memorable stories.

One woman, sitting on a pillow in the middle of the circle, recounted how a couple in her neighborhood, who’d been married for 65 years, “suicided together.” They were both members of the Hemlock Society, and they left detailed notes. The sheriff who arrived on the scene apparently said he had never felt so much love in a room. “As you can imagine,” the woman said, “this stirred up quite a bit of controversy and conversation in the neighborhood.”

Another participant spoke of a doctor who told people when and how he was going to die. The day he took his medication, his wife left and went away, in the company of other people, because if she would have been present, she could have been charged as an accessory.

I thought the question about how we would like to die was the most challenging. I started with the usual answer, the one most people give.

In bed, at home, in my sleep. WIth no warning.

But then I recalled my father’s death, where I was in the room at Evanston Hospital, with my mom and two of my brothers, and we were holding his hands and feet as he took his last breath. We could feel the warmth draining from his body. Being part of his death was one of the most powerful and profound experiences of my life, so I changed my answer. Said I’d like to die in the company of loved ones. At home. With plenty of morphine for the pain, I added.

The facilitator cited a recent California poll, showing that more than 70 percent of people would prefer to die at home in their beds. But in fact, about 70 percent die in a hospital.

You might think it would be morbid to sit inside on a sunny afternoon and discuss death, but for me, it was uplifting and fascinating. Death and how we want to die was on the agenda, but mostly we talked about how we want to live.

Find out more about Death Cafe at deathcafe.com.

(Also posted at johnbyrnebarry.com)

Comments

Thanks

I enjoyed your writing!

Posted by Cynthia Damon